Giardia

Synopsis

CAPC Recommends

- Parasite testing should follow general guidelines.

- Treat all symptomatic dogs with recommended medication and protocol. See treatment section for more information on appropriate protocols.

- Follow up fecal flotation testing may be done after the completion of therapy if clinical signs have not resolved.

- In cases where repeated infection is apparent, treatment combined with bathing and proper feces removal from the environment should be considered to prevent reinfection.

Stages

- Trophozoite—motile stage in small intestine

- Cysts—resistant stage for environmental transmission

Prevalence

- Giardia duodenalis infection is common in dogs.

- Regional differences in Giardia prevalence exist, but infections in dogs with clinical signs averaged 15.6% in dogs in the US. Overall, the most common intestinal parasite in dogs were Giardia (8.1%), and in urban parks Giardia spp. was present in 24.7% of dogs attending parks in Calgary, Canada.

- Animals in shelters, breeding facilities, kennels and catteries are more likely to carry Giardia duodenalis, and studies have found an increased prevalence among dogs that visit dog parks.

Click here to view our Prevalence Maps and to sign up for updates on reported cases in your area

Host Associations and Transmission Between Hosts

- Giardia exists in different "assemblages," which vary in their infectivity for animals and humans. Dogs have mainly Assemblages A1, C and D. However, some studies have identified human Assemblages of Giardia in canine fecal samples.

- The total number of Giardia strains and host-infectivity ranges is unknown.

- Transmission occurs upon ingestion of cysts shed by animals or humans.

- Cysts are acquired from fecal-contaminated water, food, or fomites or through self-grooming.

- Dog strains are not known to infect cats, and cat strains are not known to infect dogs.

- Human infections are primarily acquired from other humans; transmission from dogs to humans appears to be rare.

Molecular Characterization

Each assemblage (A-H) is capable of infecting certain species, and some assemblages are more commonly seen than others.

Some sub-assemblages have been shown to be zoonotic. Assemblage testing is commercially available.

Site of Infection and Pathogenesis

- Trophozoites attach to the surface of enterocytes in the small intestine, usually in the proximal portion.

- Attachment causes damage to enterocytes, resulting in functional changes and blunting of intestinal villi, which leads to maldigestion, malabsorption, and diarrhea.

- There are no intracellular stages.

- There are no infections of other tissues, except very rare cases of ectopic infection following intestinal perforation attributable to other causes.

Diagnosis

- Giardiasis is commonly misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed because of intermittent shedding and difficulty identifying cysts and trophozoites. Yeast may be mistaken for Giardia cysts due to their similar size and shape; however, yeast often show evidence of budding and do not have the internal structures seen in Giardia (i.e., median bodies, two to four nuclei).

- Trophozoites are usually 12 to 18 µm by 10 to 12 µm in size. They are motile, flagellated organisms that are teardrop or pear-shaped. Trophozoites are bilaterally symmetrical, have a large ventral adhesive disc, and have two nuclei, each with a large endosome. They also have a pair of transverse, dark-staining median bodies.

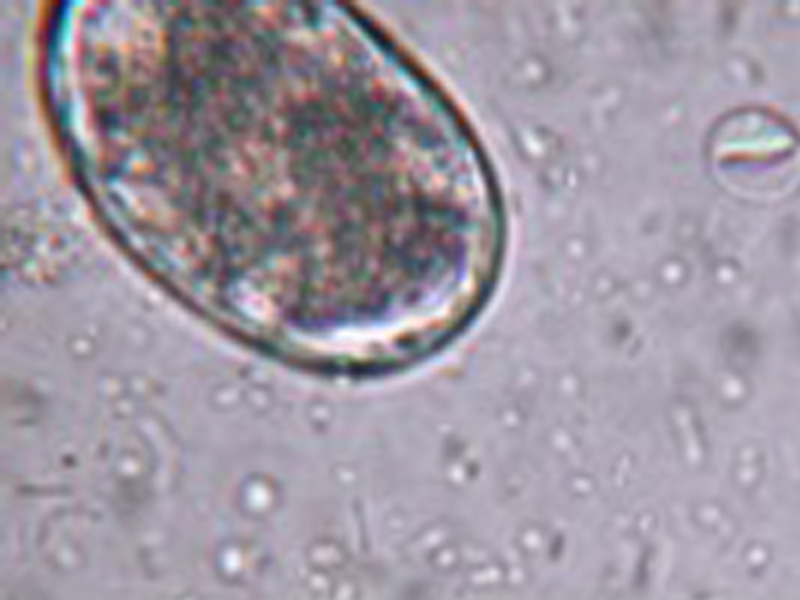

- Cysts are ellipsoidal, nonmotile, and contain two to four nuclei along with long and short curved rods. They are 8 to 12 µm by 7 to 10 µm in size and possess a thick refractile wall.

- Dogs may have subclinical infections and show no signs of disease.

- Various tests are used, including direct smear (with or without a fixative stain), fecal flotation via centrifugation, fecal ELISA, direct fluorescent antibody assay, and PCR.

- CAPC recommends testing symptomatic (intermittently or consistently diarrheic) dogs with a combination of direct smear, fecal flotation with centrifugation, and a sensitive, specific fecal ELISA or by PCR optimized for use in companion animals. Repeat testing performed over several (usually alternating) days may be necessary to identify infection.

- Direct smear:

- Direct smear is used primarily for detection of trophozoites in diarrheic stools.

- Use a small sample of fresh, unrefrigerated feces (preferably less than 30 minutes old).

- Mix sample into two to three drops of saline (not water) on a glass slide to make a fine suspension, and add a coverslip (a 22 by 40 mm coverslip works well).

- A Lugol’s iodine stain may be added to aid in identification.

- Fecal flotation with centrifugation techniques:

- This method is used primarily for detection of cysts in solid or semisolid stools.

- Mix 1 to 5 g feces and 10 ml of flotation solution (ZnSO4 sp.gr. 1.18; sugar sp. gr. 1.25) and filter/strain into a 15-ml centrifuge tube. ZnSO4 is preferred, as sugar solution will collapse the Giardia cysts, albeit in a characteristic way.

- Top off with flotation solution to form a slightly positive meniscus, add coverslip, and centrifuge for 5 minutes at 1500 to 2000 rpm.

- If desired, a Lugol’s iodine stain may be added to aid identification at 40x.

- Fecal ELISA:

- Giardia ELISA assays are approved and commercially available for patient-side testing in dogs and cats. Many diagnostic laboratories also use various ELISA microtiter well assays that have been internally validated for the detection of giardiasis in dogs and cats.

- Commercially available fixative stains (e.g. Proto-fix™) are also useful for microscopic diagnosis.

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) assays can also be used to amplify Giardia species DNA in feces and are available in commercial laboratories and in some point-of-care platforms. Additionally, some PCR tests may determine whether the Giardia subtype is potentially zoonotic.

Treatment

- No drugs are approved for treatment of giardiasis in dogs in the United States.

- Metronidazole (10-25 mg/kg BID 5-8 days) is the most commonly used extra-label therapy; however, efficacies as low as 50% to 60% are reported. Albendazole is effective against Giardia but is not safe in dogs and should not be used.

- Fenbendazole (50 mg/kg SID for 3 to 5 days) is effective in eliminating Giardia infection in dogs. Fenbendazole is approved for Giardia treatment in dogs in Europe, and available experimental evidence suggests that it is more effective than metronidazole in treating Giardia in dogs.

- Alternatively, fenbendazole (50 mg/kg SID) may be administered in combination with metronidazole (25mg/kg BID) for 5 days. This combination therapy may result in better resolution of clinical disease and cyst shedding.

- A combination of febantel, pyrantel pamoate, and praziquantel (DrontalPlus) is effective in treating Giardia in dogs when administered daily for 3 days using the dose bands indicated on the DrontalPlus label.

- Insufficient evidence is available for definitive recommendations in each clinical scenario; however, the majority opinion of the CAPC Board is that asymptomatic dogs may not require treatment.

- Factors to consider in the decision to treat include contact with vulnerable or immunocompromised humans or dogs, life style of the dog and prior treatment history. See Tynes et al, 2014 for additional information.

Follow-up Testing

- Follow up testing may be done 24-48 hours after the completion of therapy if clinical signs have not resolved. It is recommended to perform a fecal flotation with centrifugation primarily for detection of cysts in solid or semisolid stools. ELISA tests may remain positive even after treatment for variable periods of time and should not be used as a guide to determine reinfection or failure of treatment.

Refractory Treatment

- Treatment failures may result from: reinfection, inadequate drug levels, immunosuppression, drug resistance and Giardia sequestration in the gallbladder or pancreatic ducts. The presence of immunosuppression, reinfection, or sequestration can usually be determined in a clinical setting. Certain immunosuppressed patients are abnormally susceptible to giardiasis and their infections are often difficult to cure. Reinfection is common in endemic regions with high environmental contamination.

Control and Prevention

- Concomitant with treatment, animals should be bathed with shampoo to remove fecal debris and associated cysts on the last day of treatment (Payne et al., 2002).

- Remove feces daily and dispose of fecal material with municipal waste.

- Environmental areas (e.g., soil, grass, standing water) are difficult to decontaminate, but surfaces can be sanitized by steam-cleaning or use of commercially available disinfectants. Allow surfaces to dry thoroughly after cleaning.

- Post-treatment fecal examination by zinc sulfate centrifugation may be helpful in evaluating the success of therapy.

Public Health Considerations

- Human infection from a dog or cat source has not been conclusively demonstrated in North America. Canine strains of G. duodenalis are not known to be infective to immunocompetent human hosts. However, people with increased susceptibility to infection due to underlying disease should consider limiting their exposure to Giardia-infected pets.

- Advise clients to seek medical attention if they develop gastrointestinal symptoms following exposure to an infected pet.

- If both people and pets in the same household are infected, it does not necessarily imply zoonotic transmission.

- An infected person should wash hands after using the toilet and before feeding or handling animals.

Selected References

- Barr SC, Bowman DD, Heller RL, 1994. Efficacy of fenbendazole against giardiasis in dogs. Amer J Vet Res 55: 988-990.

- Carlin EP, Bowman DD, Scarlett JM, Garrett J, Lorentzen, L, 2006. Prevalence of Giardia in symptomatic dogs and cats throughout the United States as determined by the IDEXX SNAP Giardia test. Vet Therapeutics 7(3):199-206.

- Covacin, C.; Aucoin, D.P.; Elliot, A.; Thompson, R.C.A. Genotypic characterisation of Giardia from domestic dogs in the USA. Veterinary Parasitology, Volume 177, Issues 1-2, 19 April 2011: 28-32.

- Goldstein F, Thornton JJ, Szydlowski T. Biliary tract dysfunction in giardiasis. Am J Dig Dis 1978: 23:559-60.

- Nash TE, Ohl CA, Thomas E. Subramanian G, Keiser P, Moore TA. Treatment of Patients with Refractory Giardiasis. Clin Infect Dis. (2001)33(1): 22-28.

- Olson ME, Hannigan CJ, Gaviller PF, Fulton LA. (2001). The use of a Giardia vaccine as an immunotherapeutic agent in dogs. The Canadian Veterinary Journal, 42(11), 865-868.

- Payne PA, Ridley RK, Dryden MW, et al., 2002. Efficacy of a combination febantel-praziquantel-pyrantel product, with or without vaccination with a commercial Giardia vaccine, for treatment of dogs with naturally occurring giardiasis. J Amer Vet Med Assn 220:330-333.

- Saleh MN, Gilley AD, Byrnes MK, Zajac AM. Development and evaluation of a protocol for control of Giardia duodenalis in a colony of group-housed dogs at a veterinary medical college. JAVMA. 2016;249(6):644 – 649.

- Scorza V. Giardiasis. Clinicians Brief. February 2013, 71-74. http://www.cliniciansbrief.com/sites/default/files/attachments/Giardiasis.pdf.

- Simpson KW, Rishniw M, Bellosa M, et al., 2009. Influence of Enterococcus faecium SF68 probiotic on giardiasis in dogs. J Vet Internal Med 23:476-481.

- Soto JM, Dreiling DA. A case presentation of chronic cholecystitis and duodenitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1977:67:265-9.

- Tysnes KR, Skancke E, Robertson LJ. Subclinical Giardia in dogs: a veterinary conundrum relevant to human infection. Trends in Parasitol. 2014. 30(11): 520-527.

- Giardiasis – The Center for Food Security and Public Health. www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/giardiasis.pdf.

Synopsis

CAPC Recommends

- Parasite testing should follow general guidelines.

- Treat all symptomatic dogs with recommended medication and protocol. See treatment section for more information on appropriate protocols.

- Follow up fecal flotation testing may be done after the completion of therapy if clinical signs have not resolved.

- In cases where repeated infection is apparent, treatment combined with bathing and proper feces removal from the environment should be considered to prevent reinfection.

Stages

- Trophozoite—motile stage in small intestine

- Cysts—resistant stage for environmental transmission

Prevalence

- Giardia duodenalis infection is common in dogs.

- Regional differences in Giardia prevalence exist, but infections in dogs with clinical signs averaged 15.6% in dogs in the US. Overall, the most common intestinal parasite in dogs were Giardia (8.1%), and in urban parks Giardia spp. was present in 24.7% of dogs attending parks in Calgary, Canada.

- Animals in shelters, breeding facilities, kennels and catteries are more likely to carry Giardia duodenalis, and studies have found an increased prevalence among dogs that visit dog parks.

Click here to view our Prevalence Maps and to sign up for updates on reported cases in your area

Host Associations and Transmission Between Hosts

- Giardia exists in different "assemblages," which vary in their infectivity for animals and humans. Dogs have mainly Assemblages A1, C and D. However, some studies have identified human Assemblages of Giardia in canine fecal samples.

- The total number of Giardia strains and host-infectivity ranges is unknown.

- Transmission occurs upon ingestion of cysts shed by animals or humans.

- Cysts are acquired from fecal-contaminated water, food, or fomites or through self-grooming.

- Dog strains are not known to infect cats, and cat strains are not known to infect dogs.

- Human infections are primarily acquired from other humans; transmission from dogs to humans appears to be rare.

Molecular Characterization

Each assemblage (A-H) is capable of infecting certain species, and some assemblages are more commonly seen than others.

Some sub-assemblages have been shown to be zoonotic. Assemblage testing is commercially available.

Site of Infection and Pathogenesis

- Trophozoites attach to the surface of enterocytes in the small intestine, usually in the proximal portion.

- Attachment causes damage to enterocytes, resulting in functional changes and blunting of intestinal villi, which leads to maldigestion, malabsorption, and diarrhea.

- There are no intracellular stages.

- There are no infections of other tissues, except very rare cases of ectopic infection following intestinal perforation attributable to other causes.

Diagnosis

- Giardiasis is commonly misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed because of intermittent shedding and difficulty identifying cysts and trophozoites. Yeast may be mistaken for Giardia cysts due to their similar size and shape; however, yeast often show evidence of budding and do not have the internal structures seen in Giardia (i.e., median bodies, two to four nuclei).

- Trophozoites are usually 12 to 18 µm by 10 to 12 µm in size. They are motile, flagellated organisms that are teardrop or pear-shaped. Trophozoites are bilaterally symmetrical, have a large ventral adhesive disc, and have two nuclei, each with a large endosome. They also have a pair of transverse, dark-staining median bodies.

- Cysts are ellipsoidal, nonmotile, and contain two to four nuclei along with long and short curved rods. They are 8 to 12 µm by 7 to 10 µm in size and possess a thick refractile wall.

- Dogs may have subclinical infections and show no signs of disease.

- Various tests are used, including direct smear (with or without a fixative stain), fecal flotation via centrifugation, fecal ELISA, direct fluorescent antibody assay, and PCR.

- CAPC recommends testing symptomatic (intermittently or consistently diarrheic) dogs with a combination of direct smear, fecal flotation with centrifugation, and a sensitive, specific fecal ELISA or by PCR optimized for use in companion animals. Repeat testing performed over several (usually alternating) days may be necessary to identify infection.

- Direct smear:

- Direct smear is used primarily for detection of trophozoites in diarrheic stools.

- Use a small sample of fresh, unrefrigerated feces (preferably less than 30 minutes old).

- Mix sample into two to three drops of saline (not water) on a glass slide to make a fine suspension, and add a coverslip (a 22 by 40 mm coverslip works well).

- A Lugol’s iodine stain may be added to aid in identification.

- Fecal flotation with centrifugation techniques:

- This method is used primarily for detection of cysts in solid or semisolid stools.

- Mix 1 to 5 g feces and 10 ml of flotation solution (ZnSO4 sp.gr. 1.18; sugar sp. gr. 1.25) and filter/strain into a 15-ml centrifuge tube. ZnSO4 is preferred, as sugar solution will collapse the Giardia cysts, albeit in a characteristic way.

- Top off with flotation solution to form a slightly positive meniscus, add coverslip, and centrifuge for 5 minutes at 1500 to 2000 rpm.

- If desired, a Lugol’s iodine stain may be added to aid identification at 40x.

- Fecal ELISA:

- Giardia ELISA assays are approved and commercially available for patient-side testing in dogs and cats. Many diagnostic laboratories also use various ELISA microtiter well assays that have been internally validated for the detection of giardiasis in dogs and cats.

- Commercially available fixative stains (e.g. Proto-fix™) are also useful for microscopic diagnosis.

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) assays can also be used to amplify Giardia species DNA in feces and are available in commercial laboratories and in some point-of-care platforms. Additionally, some PCR tests may determine whether the Giardia subtype is potentially zoonotic.

Treatment

- No drugs are approved for treatment of giardiasis in dogs in the United States.

- Metronidazole (10-25 mg/kg BID 5-8 days) is the most commonly used extra-label therapy; however, efficacies as low as 50% to 60% are reported. Albendazole is effective against Giardia but is not safe in dogs and should not be used.

- Fenbendazole (50 mg/kg SID for 3 to 5 days) is effective in eliminating Giardia infection in dogs. Fenbendazole is approved for Giardia treatment in dogs in Europe, and available experimental evidence suggests that it is more effective than metronidazole in treating Giardia in dogs.

- Alternatively, fenbendazole (50 mg/kg SID) may be administered in combination with metronidazole (25mg/kg BID) for 5 days. This combination therapy may result in better resolution of clinical disease and cyst shedding.

- A combination of febantel, pyrantel pamoate, and praziquantel (DrontalPlus) is effective in treating Giardia in dogs when administered daily for 3 days using the dose bands indicated on the DrontalPlus label.

- Insufficient evidence is available for definitive recommendations in each clinical scenario; however, the majority opinion of the CAPC Board is that asymptomatic dogs may not require treatment.

- Factors to consider in the decision to treat include contact with vulnerable or immunocompromised humans or dogs, life style of the dog and prior treatment history. See Tynes et al, 2014 for additional information.

Follow-up Testing

- Follow up testing may be done 24-48 hours after the completion of therapy if clinical signs have not resolved. It is recommended to perform a fecal flotation with centrifugation primarily for detection of cysts in solid or semisolid stools. ELISA tests may remain positive even after treatment for variable periods of time and should not be used as a guide to determine reinfection or failure of treatment.

Refractory Treatment

- Treatment failures may result from: reinfection, inadequate drug levels, immunosuppression, drug resistance and Giardia sequestration in the gallbladder or pancreatic ducts. The presence of immunosuppression, reinfection, or sequestration can usually be determined in a clinical setting. Certain immunosuppressed patients are abnormally susceptible to giardiasis and their infections are often difficult to cure. Reinfection is common in endemic regions with high environmental contamination.

Control and Prevention

- Concomitant with treatment, animals should be bathed with shampoo to remove fecal debris and associated cysts on the last day of treatment (Payne et al., 2002).

- Remove feces daily and dispose of fecal material with municipal waste.

- Environmental areas (e.g., soil, grass, standing water) are difficult to decontaminate, but surfaces can be sanitized by steam-cleaning or use of commercially available disinfectants. Allow surfaces to dry thoroughly after cleaning.

- Post-treatment fecal examination by zinc sulfate centrifugation may be helpful in evaluating the success of therapy.

Public Health Considerations

- Human infection from a dog or cat source has not been conclusively demonstrated in North America. Canine strains of G. duodenalis are not known to be infective to immunocompetent human hosts. However, people with increased susceptibility to infection due to underlying disease should consider limiting their exposure to Giardia-infected pets.

- Advise clients to seek medical attention if they develop gastrointestinal symptoms following exposure to an infected pet.

- If both people and pets in the same household are infected, it does not necessarily imply zoonotic transmission.

- An infected person should wash hands after using the toilet and before feeding or handling animals.

Selected References

- Barr SC, Bowman DD, Heller RL, 1994. Efficacy of fenbendazole against giardiasis in dogs. Amer J Vet Res 55: 988-990.

- Carlin EP, Bowman DD, Scarlett JM, Garrett J, Lorentzen, L, 2006. Prevalence of Giardia in symptomatic dogs and cats throughout the United States as determined by the IDEXX SNAP Giardia test. Vet Therapeutics 7(3):199-206.

- Covacin, C.; Aucoin, D.P.; Elliot, A.; Thompson, R.C.A. Genotypic characterisation of Giardia from domestic dogs in the USA. Veterinary Parasitology, Volume 177, Issues 1-2, 19 April 2011: 28-32.

- Goldstein F, Thornton JJ, Szydlowski T. Biliary tract dysfunction in giardiasis. Am J Dig Dis 1978: 23:559-60.

- Nash TE, Ohl CA, Thomas E. Subramanian G, Keiser P, Moore TA. Treatment of Patients with Refractory Giardiasis. Clin Infect Dis. (2001)33(1): 22-28.

- Olson ME, Hannigan CJ, Gaviller PF, Fulton LA. (2001). The use of a Giardia vaccine as an immunotherapeutic agent in dogs. The Canadian Veterinary Journal, 42(11), 865-868.

- Payne PA, Ridley RK, Dryden MW, et al., 2002. Efficacy of a combination febantel-praziquantel-pyrantel product, with or without vaccination with a commercial Giardia vaccine, for treatment of dogs with naturally occurring giardiasis. J Amer Vet Med Assn 220:330-333.

- Saleh MN, Gilley AD, Byrnes MK, Zajac AM. Development and evaluation of a protocol for control of Giardia duodenalis in a colony of group-housed dogs at a veterinary medical college. JAVMA. 2016;249(6):644 – 649.

- Scorza V. Giardiasis. Clinicians Brief. February 2013, 71-74. http://www.cliniciansbrief.com/sites/default/files/attachments/Giardiasis.pdf.

- Simpson KW, Rishniw M, Bellosa M, et al., 2009. Influence of Enterococcus faecium SF68 probiotic on giardiasis in dogs. J Vet Internal Med 23:476-481.

- Soto JM, Dreiling DA. A case presentation of chronic cholecystitis and duodenitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1977:67:265-9.

- Tysnes KR, Skancke E, Robertson LJ. Subclinical Giardia in dogs: a veterinary conundrum relevant to human infection. Trends in Parasitol. 2014. 30(11): 520-527.

- Giardiasis – The Center for Food Security and Public Health. www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/giardiasis.pdf.

Synopsis

CAPC Recommends

- Parasite testing should be performed every 6 months especially those cases with diarrhea.

- Treat all symptomatic and infected cats with recommended medication.

- Follow up fecal flotation testing should be done 24-48 hours after the completion of therapy.

- Treatment combined with bathing and proper feces removal from the environment should be instituted to prevent reinfection.

Stages

- Trophozoite - motile stage in small intestine

- Cysts - resistant stage for environmental transmission

Prevalence

- Giardia infection is common in cats.

- Regional differences in Giardia prevalence exist, but infections in cats with clinical signs averaged 10.3% in cats in the US. A regional study in western Canada reported Giardia detection in 9.9% of samples.

Click here to view our Prevalence Maps and to sign up for updates on reported cases in your area

Host Associations and Transmission Between Hosts

- A Giardia species was first identified in cats by two investigators in 1925; one investigator named it Giardia cati and the other called it Giardia felis. It is now know that Giardia duodenalis is a species complex comprising at least eight major assemblages.

- Giardia exists in different "assemblages," which vary in their infectivity for animals and humans. Cats have Assemblages A1 and F and humans are infected with Assemblages A2 and B.

- The total number of Giardia strains and host-infectivity ranges is unknown.

- Transmission occurs upon ingestion of cysts shed by animals or humans.

- Cysts are acquired from fecal-contaminated water, food, or fomites or through self-grooming.

- Cat strain (assemblage F) are not known to infect dogs, and dog strains (assemblage C and D) are not know to infect cats.

- Human infections are primarily acquired from other humans; transmission from cats to humans appears to be rare except with infection involving assemblage A1.

Molecular Characterization

Each assemblage is capable of infecting certain species, and some assemblages are more commonly seen than others.

Assemblage A-I

- Species affected: Humans and animals (cats, dogs, livestock, deer, muskrats, beavers, voles, guinea pigs, ferrets)

Assemblage A-II

- Species affected: Humans (more common than A-I)

Assemblage A-III and A-IV

- Species affected: Exclusively animals

Assemblage B

- Species affected: Humans and animals (livestock, chinchillas, beavers, marmosets, rodents)

Assemblage C and D

- Species affected: Dogs and coyotes

Assemblage E

- Species affected: Alpacas, cattle, goats, pigs, sheep

Assemblage F

- Species affected: Cats

Assemblage G

- Species affected: Rats, mice

Assemblage H

- Species affected: Seals

Source: CDC https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/...

Site of Infection and Pathogenesis

- Trophozoites attach to the surface of enterocytes in the small intestine, usually in the proximal portion.

- Attachment causes damage to enterocytes, resulting in functional changes and blunting of intestinal villi, which leads to maldigestion, malabsorption, and diarrhea.

- There are no intracellular stages.

- There are no infections of other tissues, except very rare cases of ectopic infection following intestinal perforation attributable to other causes.

Diagnosis

- Most infected cats are afebrile, do not vomit, and have normal total protein and hemogram values. Cats may have subclinical infections and show no signs of disease.

- Giardiasis is commonly misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed because of intermittent shedding and difficulty identifying cysts and trophozoites. Yeast may be mistaken for Giardia cysts due to their similar size and shape; however, yeast often show evidence of budding and do not have the internal structures seen in Giardia (i.e., median bodies, two to four nuclei).

- Trophozoites are usually 12 to 18 µm by 10 to 12 µm in size. They are motile, flagellated organisms that are teardrop or pear-shaped. Trophozoites are bilaterally symmetrical, have a large ventral adhesive disc, and have two nuclei, each with a large endosome. They also have a pair of transverse, dark-staining median bodies.

- Cysts are ellipsoidal, nonmotile, and contain two to four nuclei, along with long and short curved rods. They are 8 to 12 µm by 7 to 10 µm in size and possess a thick refractile wall.

- Various tests are used, including direct smear (with or without a fixative stain), fecal flotation via centrifugation, fecal ELISA, and direct fluorescent antibody assay, and PCR.

- CAPC recommends testing symptomatic (intermittently or consistently diarrheic) dogs and cats with a combination of direct smear, fecal flotation with centrifugation, and a sensitive, specific fecal ELISA or by PCR optimized for use in companion animals. Repeat testing performed over several (usually alternating) days may be necessary to identify infection.

- Direct smear:

- Direct smear is used primarily for detection of trophozoites in diarrheic stools.

- Use a small sample of fresh, unrefrigerated feces (preferably less than 30 minutes old).

- Mix sample into two to three drops of saline (not water) on a glass slide to make a fine suspension, and add a coverslip (a 22 by 40 mm coverslip works well).

- A Lugol’s iodine stain may be added to aid in identification.

- Fecal flotation with centrifugation techniques:

- This method is used primarily for detection of cysts in solid or semisolid stools.

- Mix 1 to 5 g feces and 10 ml of flotation solution (ZnSO4 sp.gr. 1.18; sugar sp. gr. 1.25) and filter/strain into a 15-ml centrifuge tube. ZnSO4 is preferred, as sugar solution will collapse the Giardia cysts, albeit in a characteristic way.

- Top off with flotation solution to form a slightly positive meniscus, add coverslip, and centrifuge for 5 minutes at 1500 to 2000 rpm.

- If desired, a Lugol’s iodine stain may be added to aid identification at 40x.

- Fecal ELISA:

- Giardia ELISA assays are approved and commercially available for patient-side testing in dogs and cats. Many diagnostic laboratories also use various ELISA microtiter well assays that have been internally validated for the detection of giardiasis in dogs and cats.

- Commercially available fixative stains (e.g. Proto-fix™) are also useful for microscopic diagnosis.

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) assays can also be used to amplify Giardia species DNA in feces and are available in commercial laboratories and in some point-of-care platforms. Additionally, some PCR tests may determine whether the Giardia subtype is potentially zoonotic.

- Some subassemblages have been shown to be zoonotic. Assemblage testing is commercially available.

Treatment

- No drugs are approved for treatment of giardiasis in cats in the United States.

- Metronidazole is the most commonly used extra-label therapy; however, efficacies as low as 50% to 60% are reported. Safety concerns also limit the use of metronidazole in cats. Don’t give metronidazole benzoate to pregnant or lactating cats, or those with liver disease.

- Cats suffering from epilepsy and also taking phenobarbital for seizure control should not use metronidazole benzoate because it will potentially diminish the effectiveness of anti-seizure drugs when used in combination. There is potential for an increase of side effects when used with cimetidine.

- Albendazole is effective against Giardia but is not safe in cats and should not be used.

- CAPC recommendations for treatment of cats

- Data on treatment of cats with Giardia are lacking. However, cats may be treated with either fenbendazole (50 mg/kg SID) for 5 days, metronidazole (25 mg/kg BID) for 5 days, or a combination of the two.

Fenbendazole

- Species: Feline

- Dose: 50 mg/kg

- Route: PO (oral administration)

- Interval: Q24h

- Duration: 5 days

Metronidazole

- Species: Feline

- Dose: 25 mg/kg

- Route: PO (oral administration)

- Interval: Q12h

- Duration: 5-7 days

- There is anecdotal evidence that metronidazole benzoate is tolerated better in cats than metronidazole (USP).

- Insufficient evidence is available for definitive recommendations in each clinical scenario; however, the majority opinion of the CAPC Board is that asymptomatic cats may not require treatment. If treatment is desired:

- A cat without clinical signs that has been found to be infected with Giardia may be treated with a single course of anti-giardial therapy (see above).

- If other pets live with an infected cat, all those of the same species may also be treated with a single course of anti-giardial therapy.

- Repeated courses of treatment are not indicated in cats without clinical signs.

- CAPC does not endorse routine vaccination of all pets for Giardia. However, preventive vaccination for Giardia may be useful in some specific control situations. Current data do not support the use of Giardia vaccines as part of a treatment protocol.

Follow-up Testing

- Follow up testing should be done 24-48 hours after the completion of therapy. It is recommended to perform a fecal flotation with centrifugation primarily for detection of cysts in solid or semisolid stools. ELISA tests may remain positive even after treatment for variable periods of time and should not be used as a guide to determine reinfection or failure of treatment.

Refractory Treatment

- Treatment failures may result from: reinfection, inadequate drug levels, immunosuppression, drug resistance and Giardia sequestration in the gallbladder or pancreatic ducts. The presence of immunosuppression, reinfection, or sequestration can usually be determined in a clinical setting. Certain immunosuppressed patients are abnormally susceptible to giardiasis and their infections are often difficult to cure. Reinfection is common in endemic regions with high environmental contamination.

Control and Prevention

- Concomitant with treatment, animals should be bathed with shampoo to remove fecal debris and associated cysts.

- Remove feces daily and dispose of fecal material with municipal waste.

- Environmental areas (e.g., soil, grass, standing water) are difficult to decontaminate, but surfaces can be sanitized by steam-cleaning or use of commercially available disinfectants. Allow surfaces to dry thoroughly after cleaning.

- Post-treatment fecal examination by zinc sulfate centrifugation may be helpful in evaluating the success of therapy.

Public Health Considerations

- Human infection from a cat source has not been conclusively demonstrated in North America. Cats are not treated for the purpose of preventing zoonotic transmission.

- Canine and feline strains of G. duodenalis are not known to be infective to immunocompetent human hosts. However, people with increased susceptibility to infection due to underlying disease should consider limiting their exposure to Giardia-infected pets.

- Advise clients to seek medical attention if they develop gastrointestinal symptoms following exposure to an infected pet.

- If both people and pets in the same household are infected, it does not necessarily imply zoonotic transmission.

- An infected person should wash hands after using the toilet and before feeding or handling animals.

Selected References

- Hoopes, JH, Polley, L, Wagner B, Jenkins EJ. A retrospective investigation of feline gastrointestinal parasites in western Canada. The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 2013: 54(4): 359-362.

- Payne PA, Ridley RK, Dryden MW, et al., 2002. Efficacy of a combination febantel-praziquantel-pyrantel product, with or without vaccination with a commercial Giardia vaccine, for treatment of dogs with naturally occurring giardiasis. J Amer Vet Med Assn 220:330-333.

- Simpson KW, Rishniw M, Bellosa M, et al., 2009. Influence of Enterococcus faecium SF68 probiotic on giardiasis in dogs. J Vet Internal Med 23:476-481.

- Carlin EP, Bowman DD, Scarlett JM, Garrett J, Lorentzen, L, 2006. Prevalence of Giardia in symptomatic dogs and cats throughout the United States as determined by the IDEXX SNAP Giardiatest. Vet Therapeutics 7(3):199-206.

- Covacin, C.; Aucoin, D.P.; Elliot, A.; Thompson, R.C.A. Genotypic characterisation of Giardia from domestic dogs in the USA. Veterinary Parasitology, Volume 177, Issues 1-2, 19 April 2011: 28-32.

- Giardiasis – The Center for Food Security and Public Health. www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/giardiasis.pdf.

- Scorza V. Giardiasis. Clinicians Brief. February 2013, 71-74. http://www.cliniciansbrief.com/sites/default/files/attachments/Giardiasis.pdf.

Synopsis

CAPC Recommends

- Parasite testing should be performed every 6 months especially those cases with diarrhea.

- Treat all symptomatic and infected cats with recommended medication.

- Follow up fecal flotation testing should be done 24-48 hours after the completion of therapy.

- Treatment combined with bathing and proper feces removal from the environment should be instituted to prevent reinfection.

Stages

- Trophozoite - motile stage in small intestine

- Cysts - resistant stage for environmental transmission

Prevalence

- Giardia infection is common in cats.

- Regional differences in Giardia prevalence exist, but infections in cats with clinical signs averaged 10.3% in cats in the US. A regional study in western Canada reported Giardia detection in 9.9% of samples.

Click here to view our Prevalence Maps and to sign up for updates on reported cases in your area

Host Associations and Transmission Between Hosts

- A Giardia species was first identified in cats by two investigators in 1925; one investigator named it Giardia cati and the other called it Giardia felis. It is now know that Giardia duodenalis is a species complex comprising at least eight major assemblages.

- Giardia exists in different "assemblages," which vary in their infectivity for animals and humans. Cats have Assemblages A1 and F and humans are infected with Assemblages A2 and B.

- The total number of Giardia strains and host-infectivity ranges is unknown.

- Transmission occurs upon ingestion of cysts shed by animals or humans.

- Cysts are acquired from fecal-contaminated water, food, or fomites or through self-grooming.

- Cat strain (assemblage F) are not known to infect dogs, and dog strains (assemblage C and D) are not know to infect cats.

- Human infections are primarily acquired from other humans; transmission from cats to humans appears to be rare except with infection involving assemblage A1.

Molecular Characterization

Each assemblage is capable of infecting certain species, and some assemblages are more commonly seen than others.

Assemblage A-I

- Species affected: Humans and animals (cats, dogs, livestock, deer, muskrats, beavers, voles, guinea pigs, ferrets)

Assemblage A-II

- Species affected: Humans (more common than A-I)

Assemblage A-III and A-IV

- Species affected: Exclusively animals

Assemblage B

- Species affected: Humans and animals (livestock, chinchillas, beavers, marmosets, rodents)

Assemblage C and D

- Species affected: Dogs and coyotes

Assemblage E

- Species affected: Alpacas, cattle, goats, pigs, sheep

Assemblage F

- Species affected: Cats

Assemblage G

- Species affected: Rats, mice

Assemblage H

- Species affected: Seals

Source: CDC https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/...

Site of Infection and Pathogenesis

- Trophozoites attach to the surface of enterocytes in the small intestine, usually in the proximal portion.

- Attachment causes damage to enterocytes, resulting in functional changes and blunting of intestinal villi, which leads to maldigestion, malabsorption, and diarrhea.

- There are no intracellular stages.

- There are no infections of other tissues, except very rare cases of ectopic infection following intestinal perforation attributable to other causes.

Diagnosis

- Most infected cats are afebrile, do not vomit, and have normal total protein and hemogram values. Cats may have subclinical infections and show no signs of disease.

- Giardiasis is commonly misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed because of intermittent shedding and difficulty identifying cysts and trophozoites. Yeast may be mistaken for Giardia cysts due to their similar size and shape; however, yeast often show evidence of budding and do not have the internal structures seen in Giardia (i.e., median bodies, two to four nuclei).

- Trophozoites are usually 12 to 18 µm by 10 to 12 µm in size. They are motile, flagellated organisms that are teardrop or pear-shaped. Trophozoites are bilaterally symmetrical, have a large ventral adhesive disc, and have two nuclei, each with a large endosome. They also have a pair of transverse, dark-staining median bodies.

- Cysts are ellipsoidal, nonmotile, and contain two to four nuclei, along with long and short curved rods. They are 8 to 12 µm by 7 to 10 µm in size and possess a thick refractile wall.

- Various tests are used, including direct smear (with or without a fixative stain), fecal flotation via centrifugation, fecal ELISA, and direct fluorescent antibody assay, and PCR.

- CAPC recommends testing symptomatic (intermittently or consistently diarrheic) dogs and cats with a combination of direct smear, fecal flotation with centrifugation, and a sensitive, specific fecal ELISA or by PCR optimized for use in companion animals. Repeat testing performed over several (usually alternating) days may be necessary to identify infection.

- Direct smear:

- Direct smear is used primarily for detection of trophozoites in diarrheic stools.

- Use a small sample of fresh, unrefrigerated feces (preferably less than 30 minutes old).

- Mix sample into two to three drops of saline (not water) on a glass slide to make a fine suspension, and add a coverslip (a 22 by 40 mm coverslip works well).

- A Lugol’s iodine stain may be added to aid in identification.

- Fecal flotation with centrifugation techniques:

- This method is used primarily for detection of cysts in solid or semisolid stools.

- Mix 1 to 5 g feces and 10 ml of flotation solution (ZnSO4 sp.gr. 1.18; sugar sp. gr. 1.25) and filter/strain into a 15-ml centrifuge tube. ZnSO4 is preferred, as sugar solution will collapse the Giardia cysts, albeit in a characteristic way.

- Top off with flotation solution to form a slightly positive meniscus, add coverslip, and centrifuge for 5 minutes at 1500 to 2000 rpm.

- If desired, a Lugol’s iodine stain may be added to aid identification at 40x.

- Fecal ELISA:

- Giardia ELISA assays are approved and commercially available for patient-side testing in dogs and cats. Many diagnostic laboratories also use various ELISA microtiter well assays that have been internally validated for the detection of giardiasis in dogs and cats.

- Commercially available fixative stains (e.g. Proto-fix™) are also useful for microscopic diagnosis.

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) assays can also be used to amplify Giardia species DNA in feces and are available in commercial laboratories and in some point-of-care platforms. Additionally, some PCR tests may determine whether the Giardia subtype is potentially zoonotic.

- Some subassemblages have been shown to be zoonotic. Assemblage testing is commercially available.

Treatment

- No drugs are approved for treatment of giardiasis in cats in the United States.

- Metronidazole is the most commonly used extra-label therapy; however, efficacies as low as 50% to 60% are reported. Safety concerns also limit the use of metronidazole in cats. Don’t give metronidazole benzoate to pregnant or lactating cats, or those with liver disease.

- Cats suffering from epilepsy and also taking phenobarbital for seizure control should not use metronidazole benzoate because it will potentially diminish the effectiveness of anti-seizure drugs when used in combination. There is potential for an increase of side effects when used with cimetidine.

- Albendazole is effective against Giardia but is not safe in cats and should not be used.

- CAPC recommendations for treatment of cats

- Data on treatment of cats with Giardia are lacking. However, cats may be treated with either fenbendazole (50 mg/kg SID) for 5 days, metronidazole (25 mg/kg BID) for 5 days, or a combination of the two.

Fenbendazole

- Species: Feline

- Dose: 50 mg/kg

- Route: PO (oral administration)

- Interval: Q24h

- Duration: 5 days

Metronidazole

- Species: Feline

- Dose: 25 mg/kg

- Route: PO (oral administration)

- Interval: Q12h

- Duration: 5-7 days

- There is anecdotal evidence that metronidazole benzoate is tolerated better in cats than metronidazole (USP).

- Insufficient evidence is available for definitive recommendations in each clinical scenario; however, the majority opinion of the CAPC Board is that asymptomatic cats may not require treatment. If treatment is desired:

- A cat without clinical signs that has been found to be infected with Giardia may be treated with a single course of anti-giardial therapy (see above).

- If other pets live with an infected cat, all those of the same species may also be treated with a single course of anti-giardial therapy.

- Repeated courses of treatment are not indicated in cats without clinical signs.

- CAPC does not endorse routine vaccination of all pets for Giardia. However, preventive vaccination for Giardia may be useful in some specific control situations. Current data do not support the use of Giardia vaccines as part of a treatment protocol.

Follow-up Testing

- Follow up testing should be done 24-48 hours after the completion of therapy. It is recommended to perform a fecal flotation with centrifugation primarily for detection of cysts in solid or semisolid stools. ELISA tests may remain positive even after treatment for variable periods of time and should not be used as a guide to determine reinfection or failure of treatment.

Refractory Treatment

- Treatment failures may result from: reinfection, inadequate drug levels, immunosuppression, drug resistance and Giardia sequestration in the gallbladder or pancreatic ducts. The presence of immunosuppression, reinfection, or sequestration can usually be determined in a clinical setting. Certain immunosuppressed patients are abnormally susceptible to giardiasis and their infections are often difficult to cure. Reinfection is common in endemic regions with high environmental contamination.

Control and Prevention

- Concomitant with treatment, animals should be bathed with shampoo to remove fecal debris and associated cysts.

- Remove feces daily and dispose of fecal material with municipal waste.

- Environmental areas (e.g., soil, grass, standing water) are difficult to decontaminate, but surfaces can be sanitized by steam-cleaning or use of commercially available disinfectants. Allow surfaces to dry thoroughly after cleaning.

- Post-treatment fecal examination by zinc sulfate centrifugation may be helpful in evaluating the success of therapy.

Public Health Considerations

- Human infection from a cat source has not been conclusively demonstrated in North America. Cats are not treated for the purpose of preventing zoonotic transmission.

- Canine and feline strains of G. duodenalis are not known to be infective to immunocompetent human hosts. However, people with increased susceptibility to infection due to underlying disease should consider limiting their exposure to Giardia-infected pets.

- Advise clients to seek medical attention if they develop gastrointestinal symptoms following exposure to an infected pet.

- If both people and pets in the same household are infected, it does not necessarily imply zoonotic transmission.

- An infected person should wash hands after using the toilet and before feeding or handling animals.

Selected References

- Hoopes, JH, Polley, L, Wagner B, Jenkins EJ. A retrospective investigation of feline gastrointestinal parasites in western Canada. The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 2013: 54(4): 359-362.

- Payne PA, Ridley RK, Dryden MW, et al., 2002. Efficacy of a combination febantel-praziquantel-pyrantel product, with or without vaccination with a commercial Giardia vaccine, for treatment of dogs with naturally occurring giardiasis. J Amer Vet Med Assn 220:330-333.

- Simpson KW, Rishniw M, Bellosa M, et al., 2009. Influence of Enterococcus faecium SF68 probiotic on giardiasis in dogs. J Vet Internal Med 23:476-481.

- Carlin EP, Bowman DD, Scarlett JM, Garrett J, Lorentzen, L, 2006. Prevalence of Giardia in symptomatic dogs and cats throughout the United States as determined by the IDEXX SNAP Giardiatest. Vet Therapeutics 7(3):199-206.

- Covacin, C.; Aucoin, D.P.; Elliot, A.; Thompson, R.C.A. Genotypic characterisation of Giardia from domestic dogs in the USA. Veterinary Parasitology, Volume 177, Issues 1-2, 19 April 2011: 28-32.

- Giardiasis – The Center for Food Security and Public Health. www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/giardiasis.pdf.

- Scorza V. Giardiasis. Clinicians Brief. February 2013, 71-74. http://www.cliniciansbrief.com/sites/default/files/attachments/Giardiasis.pdf.